World War I

at Home

PRESENTED BY: MATTHEW RUANE, PhD

MP3

Narrated by Matthew Ruane

NAVIGATION

Back to top

Declining U.S. Neutrality

Events Immediately Preceding

U.S. Entry to WWI

U.S. Participation in WWI

World War I at Home

World War I Begins

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary

With His Family, 1908

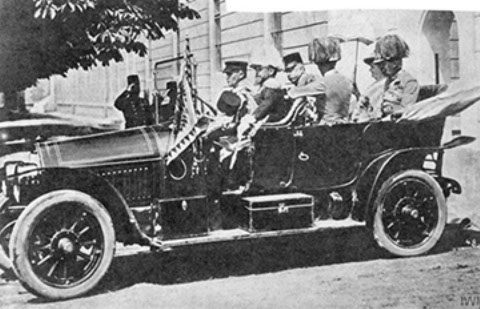

The Archduke's Motorcade Shortly Before the Assassination

The Arrest of Gavrilo Princip

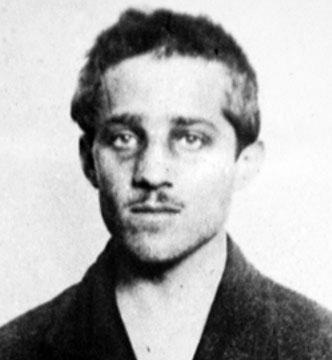

Gavrilo Princip

News of the Assassination as it Appears

in The Democratic Banner

<

>

In late June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary and his wife were on a state visit in Bosnia, traveling to the city of Sarajevo, when a young Serbian nationalist named Gavrilo Princip assassinated the couple. This set in motion a series of events that had been slowly simmering since 1871, where conflicts over trade, colonies, and the emergence of a complicated alliance system had split Europe into two large, armed camps. On July 23, 1914, the Austro-Hungarian government delivered a harshly worded ultimatum to Serbia demanding that the Serbian government agree to 10 demands meant to root out any potential future threats to Austria-Hungary. While Serbia eventually agreed to eight out of 10 demands, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914.

Europe’s intricate system of alliances came into play at this point. Serbia called upon her ally Russia for aid; Russia responded by mobilizing her army of one million men. Germany demanded that Russia stand down; Russia’s inability to do so forced Germany to declare war against Russia and Russia’s ally, France. Russia and France responded by declaring war on Austria-Hungary and Germany. Great Britain reluctantly entered the war on the side of France and Russia after Germany invaded neutral Belgium. By August 4, 1914, all of Europe was aflame. The Great War, as it was known in 1914, had begun.

Declining U.S. Neutrality

President Woodrow Wilson immediately proclaimed America’s neutrality and called on the nation to be neutral “in thought, as well as action.” While the majority of Americans wanted to stay out of the war, Wilson’s admonition to remain neutral in thought proved more difficult. America had long-standing ties to Great Britain: these ties included ancestry, language, and a history of American travel to the British Isles. British propaganda further encouraged these ties. However, many German Americans and Irish Americans were opposed to the British war effort for similar reasons to those who supported British efforts. The pro-British and pro-French Wilson administration made neutrality difficult, as did the large number of military orders for weapons and supplies from the British government. Despite its official claims of neutrality, America became the Allied arsenal and bank, while Germany protested these violations of America’s so-called neutrality.

By 1917, the U.S. government was preparing to go to war with strong popular support. What had caused this dramatic turnabout? First of all, President Wilson’s vision of a world order built on American political and economic values conflicted with his commitment to neutrality. The international system that he favored – one based on liberalism, democracy, and freedom for American enterprise – would have been impossible in a world dominated by imperial Germany. Further, Wilson gradually became convinced that even an Allied victory would not ensure a liberal peace without U.S. participation in the postwar settlement.

The most important issue, however, that dragged the U.S. into the war was the alleged violations of neutral rights on the high seas. Within days of the war breaking out in 1914, the British Navy seized American merchant ships bound for Germany, declaring their cargo contraband. Britain proclaimed that the North Sea was a war zone and off limits to neutral shipping. By March 1915, the British had established a successful naval blockade of German ports. Yet it was Germany, not England, that ultimately violated the American concept of neutral rights to the point that Americans demanded war in 1917.

While the American focus was on neutral rights and the war at sea, the land war in Europe degenerated into a costly stalemate on the Western Front. The German High Command initially planned to defeat the French and British in the autumn of 1914, but in the face of dogged Allied resistance, the German offensive bogged down. Both sides formed a line of trenches snaking across more than 600 miles of Belgium and France, from the English Channel to the Swiss border. Occasionally offenses – such as the Second Ypres in 1915, Verdun in 1916, and the Somme in July 1916 – gained a little ground while inflicting a terrible human toll on both the attackers and defenders. On the Eastern Front, the Russian army was slowly being destroyed by the German and Austro-Hungarian armies, with millions of casualties as the cost of a war of movement.

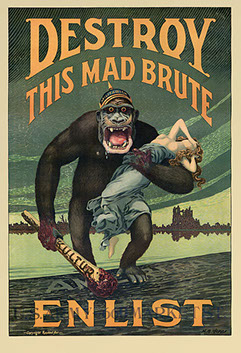

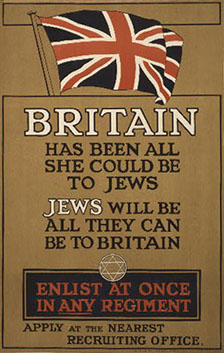

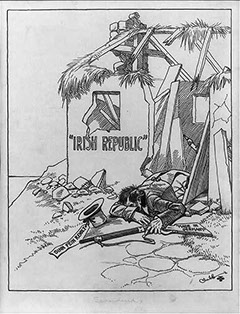

In the struggle to capture the minds of Americans, the British stepped up their propaganda campaign. Britain made a misstep in 1916 with its crushing of the Irish Easter Rebellion in April and restrictions on American trade with Germany and her allies. The emergence of the antiwar Woman’s Peace Party, along with the American Union Against Militarism, further damaged British diplomatic efforts to secure U.S. entry into the war. In an attempt to sway American opinion, the British produced posters and articles portraying the atrocities allegedly committed by the “Huns,” such as stabbing and stacking babies on bayonets as well as raping young Belgian nuns in their advance across Europe. However, women like Jane Addams and socialists like Eugene Debs, and even businessmen like Andrew Carnegie and Henry Ford, all continued to demand America remain neutral and at peace.

.jpg?crc=373316687)

President Woodrow Wilson, 1912

U.S. Army Enlistment Poster

U.S. Army Enlistment Poster

British Army Enlistment Poster

British Anti-German Employment Poster

Easter Rebellion Cartoon

<

>

Events Immediately Preceding

U.S. Entry to WWI

Woodrow Wilson Accepts the Democratic Party Nomination, 1916

While President Wilson campaigned for reelection on an antiwar platform in the fall of 1916, by early 1917, America was deciding whether the time for action had arrived. In early 1917, the German government took a fateful step and resumed unrestricted submarine warfare. Events then rushed forward with the speed of a torpedo heading toward its target.

January 31

Germany makes a formal announcement of resuming unrestricted submarine warfare.

German U-boat UB 14 With its Crew

February 3

America breaks off diplomatic relations with Germany.

War Ensign of the German Empire From 1903-1919

svg.jpg?crc=4147155350)

February 24

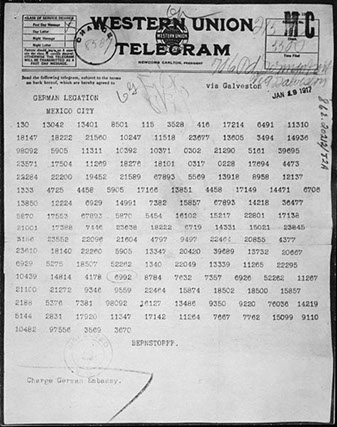

The British announce that they have decoded the Zimmermann Telegram, a message from the German foreign minister asking the Mexican government for a military alliance against the United States. If the Germans were victorious, they would help Mexico recover all the territory it had lost to the U.S. since 1848.

The Zimmermann Telegram

Late February and Early March

Several American ships are sunk by German submarines, further angering the American public and shifting public opinion towards war.

Two Type UC II Minelaying Submarines Used by the German Navy

April 2

President Wilson speaks to Congress, laying out Germany’s transgressions: violation of neutrality of the seas, interference in Mexico, interference with commerce, and the loss of American lives. Congress votes to declare war on Germany only, but a U.S. declaration of war against Austria-Hungary eventually occurs in December 1917.

President Woodrow Wilson Asking Congress to Declare War on Germany on April 2, 1917

U.S. Participation in WWI

The declaration of war in April 1917 found the U.S. military woefully unprepared. The regular army consisted of 120,000 men, only a few of whom had seen service in the Philippines or Latin America. In addition, 60,000 National Guardsmen were called up for military service. Enough ammunition was on hand for only two days of fighting, and the officer corps was filled with aged veterans. Despite attempts to increase preparedness, such as the National Defense Act of 1916, little had been accomplished by April 1917. Now the country was at war and had to rapidly build a military to fight.

Tens of thousands of women also volunteered to serve as nurses, phone operators, typists, or clerks in the military. More than 400,000 African Americans volunteered to serve, but they were drafted into segregated units and assigned as laborers and stevedores. However, some 40,000 African Americans saw combat, often assigned to French military units. One African American unit, the 369th Infantry Regiment, spent more time in combat and received more medals than any other U.S. military unit in the Great War.

Officers of the United States Army's Segregated 366th Infantry Regiment

World War I at Home

At home, the federal government began to exercise immense and growing control over the economy to meet the demands of the military. However, while initially hoping business leaders would put national interests ahead of their own, the federal government soon realized this would not happen. In July 1917, the War Industries Board was created to oversee military purchasing and ensure production efficiency. Hundreds of new government agencies were created – including the Food Administration, the Railroad Administration, and the Fuel Administration – to coordinate and streamline war production.

Demands of the war effort meant that there were labor shortages, and this meant two things: pay for workers in war industries went up substantially and women entered the workforce in larger numbers than had been seen in decades. Some women did take over formerly male jobs in factories, while most remained in traditional female occupations of typist, nurse, teacher, and domestic servant. Middle- and upper-class women volunteered to make clothing or serve with the Red Cross. One other effect of the demand for labor was the migration of African Americans from the South to northern factories, with more than 500,000 moving to places like Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland.

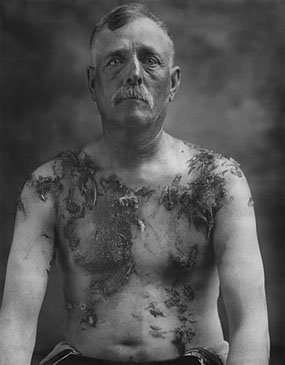

John Meintz Was Tarred and Feathered

for Not Supporting War Bond Drives

President Wilson and his advisers began a campaign to silence dissent toward the war. Hundreds of thousands of Americans – pacifists, conscientious objectors, socialists, radical labor union leaders, the poor, reformers, German Americans, and others – were subject to both government and private repression. The Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel, used propaganda in the form of posters, pamphlets, and films to encourage patriotism, and even told people to spy on their neighbors and report unpatriotic behavior to the government. Some Americans became almost hysterical in their hatred of all things German. German Americans were forced to kiss the flag or recite the Pledge of Allegiance, and German books vanished from libraries. Some were tarred and feathered, and others were beaten. Hamburgers and sauerkraut became known as “liberty sandwiches” and “liberty cabbage,” while towns like Berlin, Iowa were renamed (Berlin became Lincoln, Iowa). A popular evangelist even declared, “If you turn hell upside down you will find ‘Made in Germany’ stamped on the bottom.”

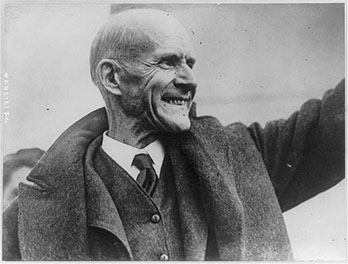

To combat critics of the war, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. The first act forbade any attempt to interfere with the draft or send treasonous materials through the mail. The second made it a crime to interfere with the sale of war bonds or use any language to describe the U.S. government, flag, or military in “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive” terms. The U.S. government also went after unions, such as the International Workers of the World, and the Socialist Party, viewing them as unpatriotic. Eugene Debs was arrested under the terms of the Espionage Act for supporting socialism and calling for free speech, including the right to criticize the government. Debs was sentenced to 10 years in prison, though he would be pardoned in 1921.

Eugene Debs Being Released From Prison